Updated for 2026. Practical tips, expert context, and honest advice for planning your visit to Machu Picchu, the fabled Inca sanctuary high in the Peruvian Andes.

Why Machu Picchu still captivates

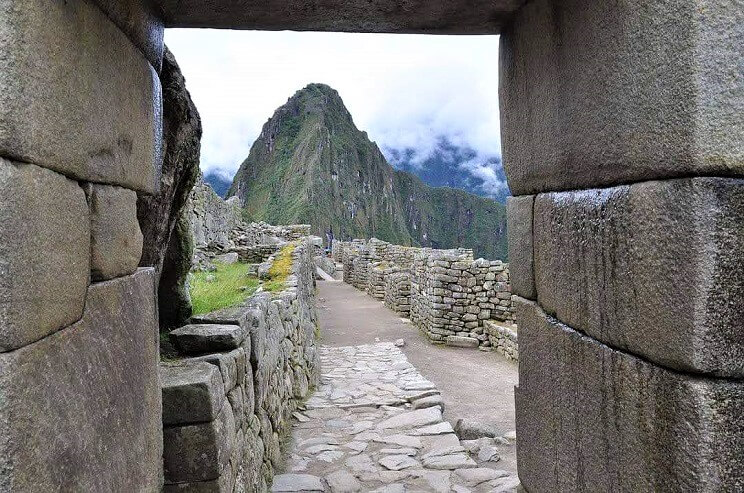

Machu Picchu isn’t just a postcard view; it’s a masterclass in Andean engineering and sacred landscape design. Set at 2,430 m (7,970 ft) on a knife-edge ridge between Machu Picchu and Huayna Picchu mountains, the citadel balances dramatic scenery with precise urban planning, stonework, and hydrology. Today, archaeologists widely view it as a royal estate and ritual center of the Inca elite—an intimate, carefully curated world where politics, ceremony, astronomy, and nature blended seamlessly.

Quick take: Plan at least 2 days in the area—one for arrival and acclimatization in Aguas Calientes (Machu Picchu Pueblo), and one for your timed-entry circuit inside the site. Add a Sacred Valley day if you can.

Fast facts

- Altitude: 2,430 m / 7,970 ft

- Era: 15th–16th centuries (occupation evidence around 1420–1530 CE)

- UNESCO status: Mixed Cultural & Natural World Heritage (since 1983)

- Primary function (consensus): Royal estate/ritual center tied to the Inca ruler Pachacuti and his lineage

- Engineering feat: Roughly 60% of the work is underground—terraces, drainage, and foundations invisible to casual visitors

A short backstory: from obscurity to global icon

In July 1911, Yale scholar Hiram Bingham reached the ridge with local guidance, documented the ruins, and later publicized them internationally. The site was never truly “lost” to local communities, but Bingham’s photos and excavations unlocked worldwide attention and academic debate.

For decades, scholars dated Machu Picchu’s construction to the mid- to late-1400s. In 2021, advanced radiocarbon (AMS) dating of human remains suggested the site was in use earlier than colonial records imply, pushing key activity into the 1420s.

Historical context: The rise of the Inca empire

The construction of Machu Picchu must be seen against the backdrop of the Inca Empire’s extraordinary rise in the 15th century. Under the leadership of Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, Cusco was transformed from a regional chiefdom into the nucleus of a sprawling empire stretching from modern-day Colombia to Chile. Pachacuti initiated massive urban redesign in Cusco and pioneered sacred royal estates, of which Machu Picchu is considered the most emblematic. This was a period of rapid territorial expansion, with the Incas consolidating their rule through military might, sophisticated diplomacy, and an ideology that intertwined divine kingship with the natural world.

The citadel in its prime

At its height, Machu Picchu would have been a living, breathing center of ritual, astronomy, and leisure for the Inca elite. Farmers maintained terraces that sustained maize and potatoes, priests oversaw ceremonies aligned with the solstices, and noble families inhabited finely carved residences overlooking the Sacred Valley. The seamless integration of architecture with the surrounding peaks—each of which had its own spiritual significance—suggests that the entire landscape was conceived as a cosmic stage. Far from being an isolated refuge, Machu Picchu was deeply tied to the spiritual and political fabric of the empire.

Abandonment and rediscovery

Machu Picchu’s decline remains a subject of debate. Some argue it was abandoned during the Spanish conquest in the 16th century, possibly due to epidemics or political instability. Others suggest it was deliberately left behind as Cusco became the focal point of resistance and eventual colonial transformation. Whatever the cause, the sanctuary gradually faded from imperial memory, though local communities always knew of its existence. When Hiram Bingham reintroduced Machu Picchu to the world in 1911, he reignited global fascination. His expeditions—backed by Yale and National Geographic—helped cement the citadel’s reputation as a symbol of Inca brilliance and mystery.

What was Machu Picchu for?

Scholars point to a royal retreat and ceremonial complex connected to the Inca court—part political theater, part sacred observatory. Features like the Temple of the Sun, Intihuatana («hitching post of the sun»), ritual fountains, and agricultural terraces show a city built to align with mountains, solstices, and water cycles. For deeper interpretations, classic works by Hiram Bingham, Johan Reinhard, and the Yale Peabody Museum collection synthesize field research, archaeoastronomy, and museum studies.

Anatomy of the site: what you’ll actually see

- Sacred precincts: The Sun Temple’s curved masonry and trapezoidal windows, the Intihuatana stone, and ritual fountains.

- Residential & service sectors: Fine ashlar walls in elite residences, plus storage, workshops, and agricultural areas.

- Terraces & drainage: Terracing stabilizes slopes and optimizes microclimates; subsurface drains wick away heavy Andean rains—why the city endures.

- Panoramas: Classic vantage points along the upper terraces and the Guardhouse. Circuit routes now structure how you access them (see below).

Pro tip: If sunrise views matter to you, plan a very early entry and stay flexible with weather; mist often clears mid‑morning.

How visiting works in 2025: tickets, circuits, caps

Peru’s Ministry of Culture manages access via timed-entry tickets and predefined circuits. Since June 1, 2024, there are 3 main circuits with 10 sub‑routes. Daily capacity in peak season reaches up to ~5,600 visitors, with lower caps off‑peak. Always buy on the official government website and select your circuit at purchase.

Essential steps:

- Choose your circuit (Panoramic, Classic, or Royalty) based on interests and walking tolerance.

- Pick a time slot (morning or afternoon waves are common). Arrive early with passport and QR code.

- Consider mountain add‑ons like Huayna Picchu or Huchuy Picchu when available (separate quotas).

- Bring your printed or digital ticket; name must match your passport.

Best time to go

- Dry season (May–September): Clearer skies, colder mornings, busiest crowds—book trains and tickets far in advance.

- Shoulder months (April, October): Great compromise for visibility vs. crowds.

- Wet season (Nov–March): Lush landscapes, frequent showers; Inca Trail closures typically affect February.

Build in time in the Sacred Valley to acclimatize before your visit—see our 2‑Day Sacred Valley & Machu Picchu tour or the broader 12‑Day Southern Peru itinerary.

Responsible travel: protect the sanctuary

- Stick to your circuit and follow your guide’s instructions; stepping off trails damages sensitive areas.

- Pack in, pack out. No single‑use plastics or food inside the core areas.

- Footwear: Grippy-lug soles help on wet stone; walking sticks must have rubber tips (check current rules).

- Altitude: Take precautions to prevent high‑altitude sickness—hydrate, go easy on alcohol, and acclimatize in the Valley first.

Key references & further reading

- National Geographic overview articles and explainers on engineering, purpose, and discoveries.

- UNESCO World Heritage dossier for official facts on altitude, boundaries, and values.

- Research updates on radiocarbon dating that recalibrate the site’s early use window.

- Classic books for context and debates: Hiram Bingham’s Lost City of the Incas; Johan Reinhard’s Machu Picchu: Exploring an Ancient Sacred Center; Yale Peabody Museum’s Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas.

Sources

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/machu-picchu-secrets?

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/274/

- https://news.yale.edu/2021/08/04/machu-picchu-older-expected-study-reveals

- https://www.wired.com/2008/07/july-24-1911-hiram-bingham-discovers-machu-picchu/?

- https://www.perurail.com/tickets-to-machu-picchu/?